Did you know that I don’t know everything there is to know about Japanese? I know, I’m surprised too. They actually let people get PhDs without checking if they know everything there is to know these days, what a world! Here’s another secret: if I don’t write things down, I sometimes forget them. Another unconscionable truth which causes me great embarrassment. Facts are facts though, so here’s the fourth post in a series where I note five things that surprised me as I do my research, and then put them down on “paper” so I don’t forget. Hopefully, as part of this process, you learn something of interest too!

1. 六借 can represent むずかしい

Recently, someone mentioned to me in a discussion on Twitter that the word むずかしい can be written as 六借. I found this quite surprising, as while I’ve certainly encountered the word むずかしい (“difficult”) a lot, I’ve never seen it written as “six + borrow”. For any readers who are just starting out their Japanese journey, the normal way to write むずかしい (difficult) is as 難しい.

Obviously, the use of 六借 instead of 難しい is not common, and you really shouldn’t use it. On the other hand though, there’s no harm in knowing it either! Before we unpack what’s going on though, let’s open our story up a bit, because there are actually quite a few ways of writing むずかしい out there throughout Japanese history. For instance, this blog notes a passage from 1906 wherein むずかしい appears as 六ケ敷い. In this representation, 六 represents むつ (as in, how we now count “6 generic objects” but without the っ), ケ is our か, and 敷 is working as し, referencing the reading found in verbs like 敷く (shiku). The final い is, of course, then just い.

If you’re reading carefully, you should have noted that this would spell mutsukashii, and you’re right. But what we now usually call muzukashii was once mutsukashii. The latter is an older pronunciation and the former, which we now treat as the norm, appeared sometime during the Edo period. That said, mutsukashii is still both used around Japan and recognized in dictionaries, even if it’s not the “official” pronunciation that gets put into our textbooks. Basically, when the muzukashii variant started to appear, people just said “eh, let’s keep using the same kanji”, and 六ケ敷い acquired two readings. Which isn’t surprising, of course, as writing systems update far slower than speech. So if you see 六ケ敷い out there somewhere, you kinda have to guess the author’s intented reading (or not care), just like you have to decide if you’re going read 家 as いえ or うち.

But actually though, 六借 and 六ケ敷い aren’t the only historic variants out there either. This research paper here notes that 六箇敷 and 六借敷 were also used, with 箇 and 借 standing in for か (due to their use in words like 箇所 (kasho) and 借りる (kariru)) rather than ケ. Now, these two representations are missing a final い, but that’s okay because the word didn’t have two ii at the end back then. There’s no question that they at least have the muzu/mutsu+kashi sound represented in their kanji.

But what about the 六借 version that started this whole discussion? Where’s the し in mutsu+ka(ri)? It looks like you have to add the し sound in your own brain, right? Well, actually, you have to add a lot of things in your own brain because in reality 六借 represented a number of words: it could stand for the adjective mutsukashi or the verb mutsukaru, and in classic old-written Japanese fashion you just had to figure out which reading was required from context. Indeed, as the aforementioned paper notes, using 六借 for both mutsukashi/mutuskaru comes from a technique at the time used to write the adjective ibukashi and its verb form ibukaru both as 言借. So the 六借敷 reading I started this discussion with came later. I imagine that people started adding 敷 for clarity at the end of the day, as “just figure it out” wasn’t working.

Anyway, this sort of “eh, just apply a kanji that sounds like the sound we want” is well known now as ateji, but has a long history in Japanese. The examples I’m showing aren’t random one-off ateji attempts though, but quite well attested, representing regular uses of ateji which sort of “solidified” over time. How much time? Well, in the examples searched across the Kotobank database, 六借 is attested back around 1100, and the earlier research paper has examples from 1180. It seems the compound was quite productive too, leading to things like 気六借 for kimuzukashi. So if anyone tells you Japanese writing is 難しい now, just let them know that it used to be much more 六借敷かった.

2. Where the word かたつむり comes from

In Japanese, it turns out snails are called かたつむり because they are completely unable to かたつ.

…are you still here? Sorry about that. Anyway, let me begin this post in earnest by explaining why I’m talking about snails at all. A while back I stumbled across tsumuri as a reading for the kanji 頭 (head). The reading is dead now more or less, but it is basically a 300+ year old way of saying “head” or “hair on the front of head”. Immediately upon finding out about this reading though, my brain thought “oh, so that’s why snails are call katatsumuri… because their tsumuri is kata(i)“.

That this thought of all things came into my mind should immediately tell you two things about my brain: (1) it makes strange connections, and (2) the strange connections it makes are not very good ones, because the hard part of a snail is obviously the shell not the head. Snails have, in fact, very soft heads. But realizing that I was completely wrong about my theory lead me to wonder where the word katatsumuri actually came from, which lead to this blog entry. So three cheers for making large errors!

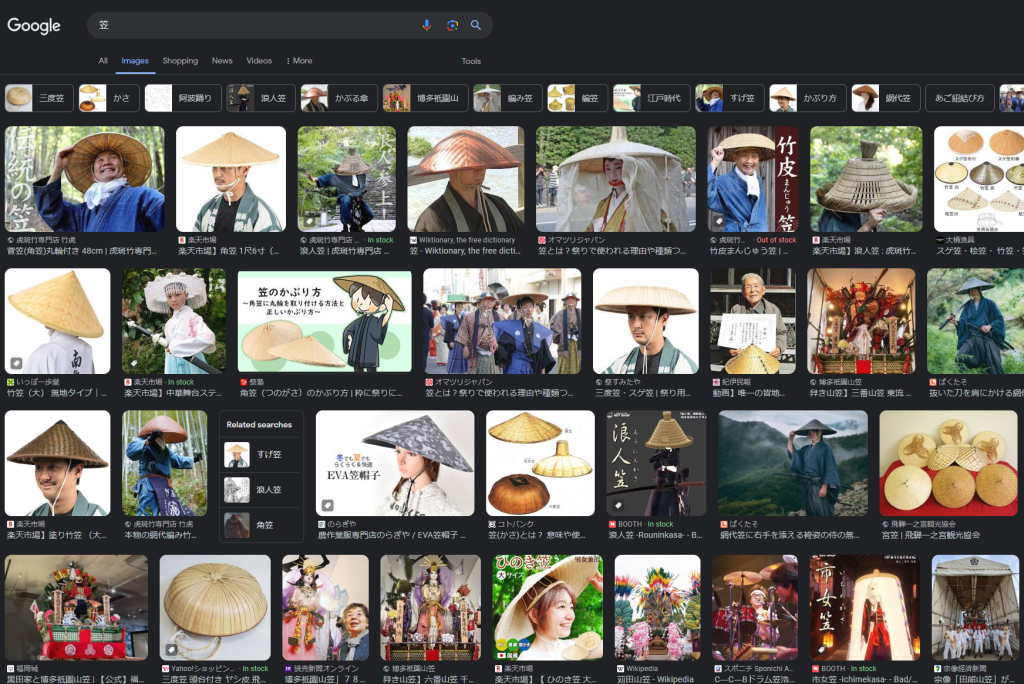

Where does katatsumuri come from then? As a word, I mean, not as an animal. We don’t know for sure, as katatsumuri has been used in Japanese for quite some time. But there are a few major guesses with at least some evidence behind them. One relates to the word 笠 (kasa), the traditional Japanese wide-brimmed hat… although I did find one source claiming the origin was 傘 (kasa, umbrellas), but I think this is a case of someone hearing “the word katatsumuri comes from kasa” and misunderstanding. In either case though, the arguments go that in the past both 笠 and 傘 were often woven in a spiral shape, which kind of looked like snail’s shell.

This kasa sound was then either combined with tsubura (now “round”), tsuburi (now “head”), or tsuburo (now not a word), which all once referred to shells. Their shared etymology is all linked to the same word that gave us 粒 (tsubu, grain/bead), and so it’s basically all “round” related. Anyway, from this combination we got something like kasa + tsuburi, and kasa somehow became kata, giving us katatsuburi which gradually changed into katatsumuri. By the way, when I say “somehow became kata“, that’s not me being lazy. I spent a long time searching, and no one else can explain it either it seems, as you can see in the Daijisen dictionary screenshot below that just says “a sound change”. I’m guessing it’s part of a larger historic sound change that affected multiple words, but I can’t pinpoint which one – sorry. If you know, please leave a comment!

Anyway, without question this “hat-shell” theory is the most popular explanation for the origin of katatsumuri. But there are others! Most of these assume, like I did, that the kata comes from katai (hard) instead of kasa (hat) – indeed, the Daijisen screenshot above mentions that possibility too. So in this interpretation, a katatsumuri is just a “hard shell”, which certainly has an attractive logic to it. There’s also the possibility of kata coming from 潟, which means “lagoon” or “inlet”, probably because snails do like moist places. Then there’s the possibility that the name comes from the fact that snails furi (振り, waive) their katatsuno (片角, “one horn”, likely “one eye stalk” here), but while interesting this theory is unlikely. Even more unlikely though is this final theory I found some random person asserting on Yahoo! Chiebukuro, claiming that the name comes from the fact that rain hitting a snail’s shell makes a katakata sound which was attached to tsumuri because a tsumu (spindle) looks like a snail’s shell.

Does that last claim sound like a bit of a reach to you? It sure does to me, and I can’t find any other claims to back it up. Still, hey, it’s not like I can prove someone wasn’t like “yo, let’s call that animal a name based on what it sounds like when hit by rain, and also include the fact that it looks a bit like a spindle, but then then let’s add a り sound too just ‘cuz”, and a bunch of Japanese people around them said “yeah okay great, I love naming things based on the sound they make when rain hits them, that’s a totally normal thing to do, especially for really tiny animals”. I can be skeptical, but stranger things have happened for sure.

Anyway, now let’s move to snail kanji. As a native Japanese word, katatsumuri had to get kanji “attached” to it, and the kanji it got were 蝸牛. But why? This obviously doesn’t align with the katatsumuri reading, as 蝸 isn’t kata and 牛 isn’t tsumuri. Basically, all that happened here is that Japan borrowed 蝸牛 from Chinese, where it is how they wrote, and still write, “snail”.

Japanese people then began reading 蝸牛 as katatsumuri as its kunyomi, or more specifically jukujikun and that was that. Indeed, 蝸 can now even be used for katatsumuri by itself. Why did Chinese people choose 蝸牛 though? Well, the kanji 蝸 is basically saying to the reader that “this is a bug that has a spiral”, just as 渦 (whirlpool) screams “water with a spiral”. As for the “cow” part, that’s less clear. People seem to think that basically a long time ago whoever chose 蝸牛 as the kanji pair thought that snails either moved a bit like cows, or their eyes look like cow horns. Or something. There’s no question that the 牛 in 蝸牛 has something to do with someone drawing some kind of a similarity between snail and cows, but it doesn’t seem like anyone is fully willing to make an authoritative claim on what that similarity was. Long story short though, because of this 蝸牛 borrowing, you can actually refer to katatsumuri as kagyuu in Japanese via each kanji’s onyomi, although no Japanese person I spoke to while researching this has actually heard this happen in real life.

Interestingly, and as you can see above, kagyuu is now the Japanese word for your cochlea too. Why? Because that bit inside your ear kinda looks like a snail’s shell. So lots of spiral links here, and if you’re Junji Ito I’m sure that is making you very happy. Thanks for reading, Junji, I appreciate it.

In closing, there are also two other names for snails in Japanese I want to cover briefly for the sake of 100% completion: dendenmushi and maimai. I don’t have the time to investigate these in depth, but Wikipedia notes, with cited sources, that a common theory is that these names came from things children would yell at snails. I know that sounds odd, but bear with me. The dendenmushi comes from children yelling at snails to come out of their shells via den! (or deyo!, depending on your source), which is an older imperative form of 出る. In contrast, maimai comes from children yelling “dance, dance (舞え! 舞え!)” at the snails, which I guess is a joke? The former sounds more plausible than the latter to me but, hey, it’s not like I have evidence for anything else on me. And if I was a bored kid thousands of years ago, I might have thought yelling at snails to dance was great fun. No judgement.

3. 可愛い is ateji

The first time I saw kawaii in kanji as 可愛い I thought “oh okay, the word literally means ‘can be loved’, got it, nifty”. Yes, I should have noted that it is odd that in 可愛い the ai from 愛い somehow is read as wai, but I just figured that at one time in history Japanese people pronounced ai as wai. The fact that 可愛 is a Chinese word too, and one with a currently similar meaning and pronunciation (kě’ài in Mandarin), certainly helped reinforce this view. But recently I found that this seductive logic is actually all wrong, so just like with my thinking that snails have hard heads or whatever my assumptions once again leave me 可哀想.

As it turns out, 可愛い is ateji, attached to the word kawaii long after the word became a thing. We know this for a number of reasons, but the most important is that kawaii doesn’t come from an origin word meaning anything like “cute” or “can be loved”. The now world-wide kawaii started out as kawahayushi and then got shortened to kawayushi, both of which worked more like kawaisou does now to refer to a feeling of pity and/or sympathy at someone’s misfortune. The kanji 可 and 愛 were nowhere to be seen, as the representations at the time were things like 顔映し. The use of 顔 or “face” here comes from the idea of “can’t turn your face away”, while 映 was used in lots of words back then which related to emotions that manifest on your face. The word 目映し (mabayushi), for instance, meant “can’t open your eyes (metaphorically, due to emotions)”, which now exists as 眩い (mabayui, dazzlingly beautiful).

Around the 1100s, the pronunciation of kawayushi became kawayui, and began seeing use to mean “pitiful” or “feeling uncomfortable”. Importantly though, this was especially “pitiful in a way that made you want to do something about it”. That is, the kind of pathetic you can’t help but want to help, not the kind of pathetic you feel contempt for. It is this feeling of compassion or a desire to help which lead to the word being gradually used more and more like the kawaii we know today, with the sound change to kawaii itself finalizing around 15-1600CE. So at that time, calling something kawaii was rooted in the idea that things that are kawaii draw out your emotional desire to protect, assist, help, etc., although now we know that what kawaii things actually do is draw out our desire to empty our wallets, as Sanrio has figured out so well. Anyway, as some part in this process, people decided that “can be loved” was a good ateji for kawaii, and added 可愛い to it even though 愛 isn’t wai. They can do that, by the way, it’s not a problem and happens all the time.

Now, at the start of this article, I mentioned that 可愛い is not from Chinese. I need to unpack this a bit here. There is a non-zero chance that Japan’s 可愛い representation is a reference to, or influenced by, Chinese’s 可愛. This theory is so popular that even Japanese Wikipedia notes a possible relationship, but I can’t help but notice that they also have a big “citation needed” flag which, if you mouse-over, has been there since 2013. This means that for over 10 years now the “from Chinese” citation has just been entirely dependent on a load-bearing とも思われる, the patron saint of lazy scholarship in Japanese, which makes me suspicious.

One the other hand, what I can say is incorrect is the persistent theory that it was actually Chinese that borrowed 可愛 from Japan. As this one random poster on Chiebukuro notes, “it’s hard to imagine 可愛い going over to China [from Japan]” as the use of 可+[verb], borrowed in other Japanese terms like 可笑しい for okashii, is a standard part of Chinese grammar. And while 可笑しい therefore looks like the word 可笑 (kěxiào) used for a similar meaning (“ridiculous”) in contemporary Mandarin, no one possibly imagines that 可笑 came from Japanese. The 可愛い to 可愛 thesis is just attractive because of a chance sound link… and potentially a bit of nationalism, but I’ll let that thought rest because investigating further wouldn’t be very 可愛い at all.

One quick thing in closing, while it may seem odd for “pathetic” to become “cute”, apparently it’s happened elsewhere too. Wiktionary notes a similar thing in Korean? I don’t have the ability to check Korean etymologies or… well… anything related to Korean, unfortunately, but it is nifty if this is real. The English sources I found were similarly unreliable unfortunately, as Wiktionary also leaves us in a state of 要出典 for their assertions about Korean.

4. There are lots of kanji for うた(う)

I recently published a piece about Ado’s song 唱, and in it I noted that there were a lot of kanji for the words うた・うたう. I didn’t have time to go into them there, but the sheer amount of kanji I found were certainly something new I learned about Japanese recently, so I’m going to talk about them here where I have space for it!

Obviously, the most common kanji for both うた and the verb うたう is 歌. This is the kanji you should use going forward for almost everything. If you use any of the other kanji here to write うた or うたう and your teacher marks you wrong, or just gives you side-eye for the rest of your time together, I take no responsibility! As you can see from the blatant Wiktionary screenshot below, 歌 comes from a word that was pronounced ga or ka in Burmese, and apparently also ka in Middle Chinese. So it’s not surprising that the kanji also has the Japanese onyomi of ka.

That said, Wiktionary also notes three other kanji for うた: 唄, 詩, and 謳, and divides them between 詩 for modern poetry, 歌 for songs and classical Japanese poems, and 唄 for shamisen songs. The 謳 is given no explanation. I would love to say “and that’s that!”, but this is far from the full story.

In reality, there are at least 22 different ways to write うた・うたう. Yes, that’s right, 22 different kanji at minimum. I didn’t make the rules here, don’t blame me. Some of these are just variant shapes of others, and some are rarely (if ever) used, much less for the specific nuance they are “supposed” to have. But they have been used sometime throughout the history of written Japanese.

So let’s jump into it. We’ll begin with the six 常用漢字: 歌, 唱, 唄, 詠, 謡, and 吟. As mentioned 歌 is the “generic” kanji you can use for everything singing related. That was easy! At this rate I’ll be done in 21 more sentences. The kanji 唱 and 唄, which have the nice little “mouth” radical there on the left that feels quite appropriate to a “sing” kanji, have a number of specific uses. The 唱 version is often seen as a pretty direct replacement for 歌, as it can be used for rhythmic singing. However, it also is able to represent the verb となえる, which means “to advocate for” or “to chant/read aloud”, so 唱 has specific uses for reading poetry etc. aloud. The use of 晶 on the left, which is where the kanji gets its on-yomi of しょう from, is supposed to be due to the kanji representing the idea of singing in a clear, loud voice.

In contrast, 唄 is linked to the singing of traditional Japanese songs, hence its use in words like 小唄 (こうた, traditional ballad), 長唄 (ながうた, longer song song with shamisen), 地唄 (じうた, folk song), or 子守唄 (こもりうた, lullaby), and older religious chants/songs which praise Buddha. That said, one thing to keep in mind here (and for all descriptions) is that these are ultimately nothing more than uses that dictionaries list. Whether the average Japanese person knows or even cares about these distinctions in their use of the kanji is up in the air. But when this person notes that a cheesecake 唱っているs its 濃厚, you can see this link between the “advocacy” or “sing the praises” meaning described earlier and the kanji choice for うたう.

This leaves us with 詠 and 謡. The kanji 詠 is probably better known for representing the verb よむ, which means “to write poetry”. Yes, that’s right, if you say “私は詩をよむ” no one knows if you read or write it. Speech bad, kanji good. By extension then, 詠う is to mean “express via poetry” (so, yes, “to sing” as a metaphor of “to write” rather than literally “to sing” I suppose) or “to read aloud as poetry” (usually without rhythm). You can see the “write” version in the recommended sentence IME produces, which notes how you can “sing of joy in poetry” via 詠う. Not real singing, you see, metaphorical singing.

Sometimes, metal bands use 詠 to be all epic and stuff too. If you want to “sing of fate”, 歌 just isn’t as dark and mysterious as 詠, and we can’t have that in our metal music.

The 咏 kanji is then just a variant of 詠. Or maybe 詠 is a variant of 咏? The website I linked at the start of this paragraph lists each as the 異体字 of the other, so who knows? It’s not like I can trace which came first from my computer here, so, whatever. Your preferred one is the original, I’m sure.

From what I can tell on Twitter, which should not be take as fact, both 詠 and 咏 see similar-ish frequencies of use, and both are definitely being used heavily for reference to poetry. My computer only gives 詠う as a “suggested input” though, so that’s probably the more “normal” one of the two very-not-normal kanji.

That said, 咏う did see use in a translated film title to mean “ode”, so it’s got that going for it at least.

The kanji 謡 is then especially for Noh songs, doubly especially forms of singing (Noh or not) when there is little to no accompanying music. The kanji 謠 you saw earlier is older version of 謡, so two-birds-one-stone here. And while I did see a few people using both of these online during attempts at making their modern rock/pop sound a bit epic, a more “traditional” (note that I didn’t say “correct”) use can be seen in this next screenshot, as it appears in a description of a video where three people chant with only light bell accompaniment in the background.

Finally, 吟 is used for singing that comes out of a closed mouth, more or less, as our good friend 今 (ima, “now”) actually original referred to things being covered or sealed. So when you 吟う you usually hum. You can see this reference to “closed mouth” in lots of words that include 吟, such as 呻吟 (しんぎん, groaning), 口吟 (こうぎん, to hum to yourself), or 低吟 (ていぎん, a low humming or singing). That said, the kanji also appears in words like 高吟 (こうぎん, loud poetry recitation) and 吟遊詩人 (ぎんゆうしじん, minstrel), so 吟 can refer to “normal” singing or songs too. But when this person notes that the insects are 吟ってんing, it’s because they are humming.

Okay, so where does that leave us? Looks like we’ve got 14 left. I hope some of them are redundant…

…and the good news is that they are! Let’s get rid of three right off the bat: the kanji 謳 is the same as 讴 and 𧦅. The 謳 version is the “correct” one, 讴 is a simplified version, and 𧦅 is what’s called a 拡張新字体. What’s a kakuchoushinjitai, you ask? Well, it’s when you take the techniques that the Japanese used to create 新字体, or the Japanese simplified characters, and apply them to kanji that aren’t on the Toyo/Joyo kanji list. For instance, do you know the kanji 区? Well it used to be 區. So clearly, 品 can become X. If we apply this to 謳, we get 𧦅, which the government will frown on you for using but still exists. Anyway, what kind of singing do these three all refer to? Lots of people extolling together. That’s why there’s so many mouths (口口口, better known as X)! Or, by extension, to assert or appeal something forcefully. For instance, this website lists the word 謳歌 (おうか, a song of praise) and both 「太平の世を謳う (to extoll a peaceful world)」 and 「効能書きが謳うような効果は、この薬からは感じられなかった (I didn’t feel the effect this medicine’s efficacy statement claimed)」 as key examples of “proper” 謳 use. This person noting that the movie The Creator 謳うs, as in sings the praises of, Americans losing a (real & metaphorical) battle is similar.

“Ah ha, Wes!”, you begin, “but what about the 讴う variant? Are Japanese people actually using that?”. Well, not really. But not 0 either. And there’s some kind of lyric that uses it too?

We then have a few more alternate versions. The 呗 kanji is just 唄, as is 㗑. Apparently, as are 𠼚, 𠼕, and 𡁭. Like I said, more than 22. But none of these are used at all. Like, most have 0 hits on GOOGLE (not Twitter, Google) for every conjugation of うたいます I could think of. At most, you can see a bit of 呗います, but from what I can tell it is mostly caused by someone writing in fonts that don’t render Japanese versions of characters.

There are then also a few うたう kanji which appear to have very specific uses, see minimal real-world application. The version 哦, for instance, appears in obscure words like 吟哦 (ぎんが, to sing loudly), and is listed in dictionaries as indicating loud singing or yelps of surprise. Are people using it to mean that on Twitter though? Is it the Japanese death metal kanji of choice for “to sing”? Well, it should be, but no. No one’s really using 哦 at all for anything. Not even in joke sentences like 我は口で哦う. I may have been the first person in history to write that, believe it or not.

The kanji 嘔 and 呕 are then also two versions of the same kanji, linked via the same simplification strategy we talked about earlier, and are actually just variants of 謳う. So the same sort of “sing the praises of”, as in “love”.

Moving on, 谣 and 䚺 are variants of the “singing Noh with no music” kanji 謡/謠. More specifically, 谣 is a simplified form and 䚺 is what Wiktionary calls a “non-classical” form, which I have no clue how to interpret. Neither are really used in Japanese now, but have been at least once, of course.

The kanji 噖 and 訡 are then, unsurprisingly, complex variants of the “humming” 吟. The key difference between them and 吟 is, to be blunt, that 吟 is actually still used in contemporary Japan. Finally, 誯 is a variant of 唱, so you can use it for “sing/advocate” but, again, no one really does. Okay, so where does that leave us? With just two left! Let’s keep this song going!

The kanji 哥 gradually evolved to mean 兄 (older brother) in Chinese, but in Japan has just been used as a variant of 歌. I mean, you can see why, right? They share the same left half! They’re almost 哥弟! Er, sorry, 兄弟! According to one person on Chiebukuro, and more believably this database entry, 哥 even appeared in the Man’yōshū as a generic 歌 replacement, with people spelling waka as 倭哥 rather than the current 和歌. More interestingly though, 哥 departs from 歌 in that it also has an on-yomi of こ. This isn’t listed in some dictionaries, but it exists as the kanji’s tōon, a type of rare on-yomi that arrived in Japan in bits and pieces after 1000AD. As a result, 哥has been used as an ateji for こ in various country names, as in 哥倫比亜 for Columbia, and 墨西哥 for Mexico. The 謌う version is then just another variant for 歌. It’s not common, but you can use it if you want, I guess. This person did for their vocaloid video!

And that’s it! Of course, I do have to end with the caveat that a lot of the use of various kanji for うたう is just vibes. Not everyone Japanese person knows or cares about the difference between each version, and some people just go “oh that’s the one I saw in [context]” and then keep using it in [context] even if they misunderstood why it appeared in [context]. You also have issues like wordplay – the Ado song I mentioned earlier uses 唱 primarily because it’s onyomi is homophonous with the English word “show”. But hey, if you want to 唱-off your kanji knowledge, there’s a lot of ways you can do that via how you decide to write うたう.

5. There is a “Y” Kanji

Let’s end on a short, exciting note. Check out this kanji: 丫! Wow, how cool! And yeah, it’s real. In fact, it’s got some pretty great uses. Well, okay, that last claim is not true. The kanji 丫 has no uses, because no one really knows about it or uses it. But, if they did, oh-ho we could have some fun because of all the potential cool uses it has. The first fun that we could have (but, again, can’t) is to represent the word ふたまた or “bifurcation”.

Cool, right! A totally common, everyday word that you use in Japanese all the time, or at least would if you could write it in one kanji instead of two. Unfortunately though, contemporary Japanese internet users aren’t taking advantage of this time-saving hack. Most posts using 丫 in Japanese are either hits of people using it in their profile names, asking how to read it, mentioning that they found a use for it… but not showing that use…

…or even just asking the good question of 丫 no one has found a good use for 丫 given that 十 and 丁 see some alternate applications.

Indeed, I can’t find a single example at all, including a website with a historical one, of people using 丫 to write “bifurcation”. You can see how 丫would work well for this use though, as it literally bifurcates. Alas! Don’t forget that 丫 does bifurcate though. Unlike the English Y, this 丫 is a three-stroke kanji, even though some fonts don’t represent the third stroke clearly. If you watch a calligrapher write it, which you can do here, you’ll clearly see three strokes.

And now that you know how to write 丫, I suppose you can use it. To show you what that might look like, here’s some examples of sentences using ふたまた from ALC, where I’ve replaced 二股 with 丫. Can anyone read these? Well, you can now, but generally no. Should you do this? Also no. But can you do this? The kanji rules certainly allow it, I suppose. The path of how to write ふたまた 丫s before you.

The other thing you can do with 丫 is refer to a haircut known as あげまき. This isn’t in fashion anymore, but involved dividing the hair left and right, hence the “bifurcate kanji”, and then tying above each ear. There are other names for this haircut, like みずら, and other kanji, as あげまき can be written as 総角 or 揚巻 too.

As you can see in this next dictionary screenshot, this hairstyle was once specifically a boys’ hairstyle, and actually has a few other kanji linked to it (or at least to its みずら reading). These are 鬟, 髻, and 丱, none of which I will (or can, to be honest) explain but I’ve linked to their Wiktionary entries if you are curious. Pretty incredible that one haircut gets four or more kanji, but I guess it was a popular style that people really liked writing about in a space-saving manner.

That said, do be a bit careful: there are multiple words (including multiple hairstyles!) which are called あげまき. The only one that we can use 丫 to represent is, of course, the “split” one that was traditionally for boys, because that’s the only あげまき meaning which refers to any kind of “split/parting”. The Meiji-era women’s あげまき, for instance, involves no parting of the hair, so you can’t use 丫 to refer to it.

And that’s about it for both 丫 and this blog post! The only thing left to mention is that 丫 has onyomi of あ, apparently, which has some odd uses. For instance, you can combine 丫 with the あげまき kanji 鬟 to get あかん or あくわん. These words can both refer to the あげまき hairstyle itself, or female servants (the hairstyle became non-gendered or switched popularity, apparently) who have the hairstyle. The word 丫頭, or あとう, is the same. Hairstyle, or female servant with the hairstyle.

Oh, and sometimes Japanese people use 丫 when non-Japanese people do, because, you know, why wouldn’t you? There are some (stage) names that include 丫, like Yatou Chan’s 丫頭, and the ラマ島 (Lamma Island in English) often appears as 南丫島, because that’s how the people who live there write its name.

And that’s, as they say, 丫ll I have to say about 丫. In fact, it’s actually 丫ll I have to say about this blog post! See you 丫ll for the next one, when I’ll talk about snacks, axolotls, thumbs, my inability to come up with punchy endings, and so much more.

If you enjoy my writing, considering subscribing to get articles sent directly to your email! We also appreciate contributions via Ko-Fi to help keep this website ad-free.